When your heart valve doesn’t open or close right, it’s not just a minor glitch-it’s a life-changing problem. Imagine a door that won’t swing fully open or keeps leaking air. That’s what happens when heart valves fail. The heart has four valves-aortic, mitral, tricuspid, and pulmonary-each designed to let blood flow in one direction only. When they stiffen, narrow, or leak, the heart has to work harder, and over time, that strain can lead to heart failure, irregular rhythms, or sudden death.

What Is Stenosis? When Valves Get Stuck

Stenosis means a valve has narrowed. The leaflets become stiff, often from calcium buildup, and can’t open fully. Blood can’t flow through easily, so the heart pumps harder to push blood past the blockage. The most common type is aortic stenosis. It affects about 2% of people over 65. In many cases, it’s not from a childhood illness or injury-it’s just aging. About 70% of cases come from calcification that slowly builds up over decades.

Severe aortic stenosis is defined by three clear numbers: a valve area smaller than 1.0 cm², a pressure difference across the valve greater than 40 mmHg, and a blood jet speed faster than 4.0 m/s. If you’re over 75 and have trouble walking up stairs without stopping to catch your breath, it might be more than just being out of shape.

Mitral stenosis is less common in the UK and US today but still widespread in developing countries. Around 80% of those cases trace back to rheumatic fever, a complication of untreated strep throat that scarred the valve years earlier. When the mitral valve narrows below 2.5 cm², blood starts backing up into the lungs, causing shortness of breath, especially when lying down. That’s called orthopnea-and it’s a red flag.

What Is Regurgitation? When Valves Leak

Regurgitation is the opposite problem: the valve doesn’t close tightly, so blood flows backward. It’s like a faulty one-way valve in a water pipe. The heart ends up pumping the same blood over and over, which exhausts it.

Aortic regurgitation lets oxygen-rich blood leak back into the left ventricle after it’s been pumped out. People often feel their heart pounding, especially at night, or get winded just walking to the kitchen. It doesn’t always cause symptoms right away, but over time, the left ventricle stretches and weakens.

Mitral regurgitation is even more common. It can be caused by a torn chordae tendineae (the strings that hold the valve in place), heart muscle damage from a past heart attack, or just wear and tear. In functional mitral regurgitation-where the valve itself is fine but the heart chamber is enlarged-the leak happens because the whole structure is out of shape. The COAPT trial showed that for these cases, a minimally invasive clip device (MitraClip) cut death rates by 32% compared to just medication.

One key difference: stenosis makes the heart work harder to push blood out; regurgitation makes it work harder to pump the same blood again. Both are dangerous, but they need different treatments.

Symptoms You Can’t Ignore

Many people with valve disease don’t feel anything until it’s advanced. That’s why it’s called a silent killer. But when symptoms do show up, they’re hard to miss.

For aortic stenosis, the classic signs are chest pain (angina), fainting (syncope), and heart failure symptoms like swelling in the legs or extreme fatigue. About half of patients with severe stenosis have one or more of these. If you’re over 65 and suddenly can’t climb stairs like you used to, don’t just blame age.

Mitral regurgitation often starts with fatigue so subtle you think you’re just tired. But by the time you’re waking up gasping for air or can’t walk across the room without stopping, it’s too late. The Cleveland Clinic found that 87% of patients with severe aortic stenosis felt they could barely manage daily tasks before treatment. After surgery, 92% said their energy bounced back within a month.

One big problem? Many patients say they were dismissed by doctors until they were nearly collapsed. A 2022 survey found 28% of valve disease patients felt ignored until symptoms became severe. If your doctor brushes off shortness of breath or unusual fatigue, get a second opinion-and ask for an echocardiogram.

Surgical Options: From Open Heart to Tiny Catheters

Treatment depends on the valve, the severity, your age, and your overall health. For decades, open-heart surgery was the only option. Now, there are less invasive choices.

Surgical valve replacement is still the gold standard for many. The surgeon opens the chest, stops the heart, replaces the bad valve with a mechanical one or a tissue valve from a pig, cow, or human donor. Mechanical valves last forever but require lifelong blood thinners. Tissue valves don’t need long-term anticoagulation but wear out in 15-20 years. If you’re under 60, your doctor will likely push for mechanical. If you’re over 70, tissue is usually preferred.

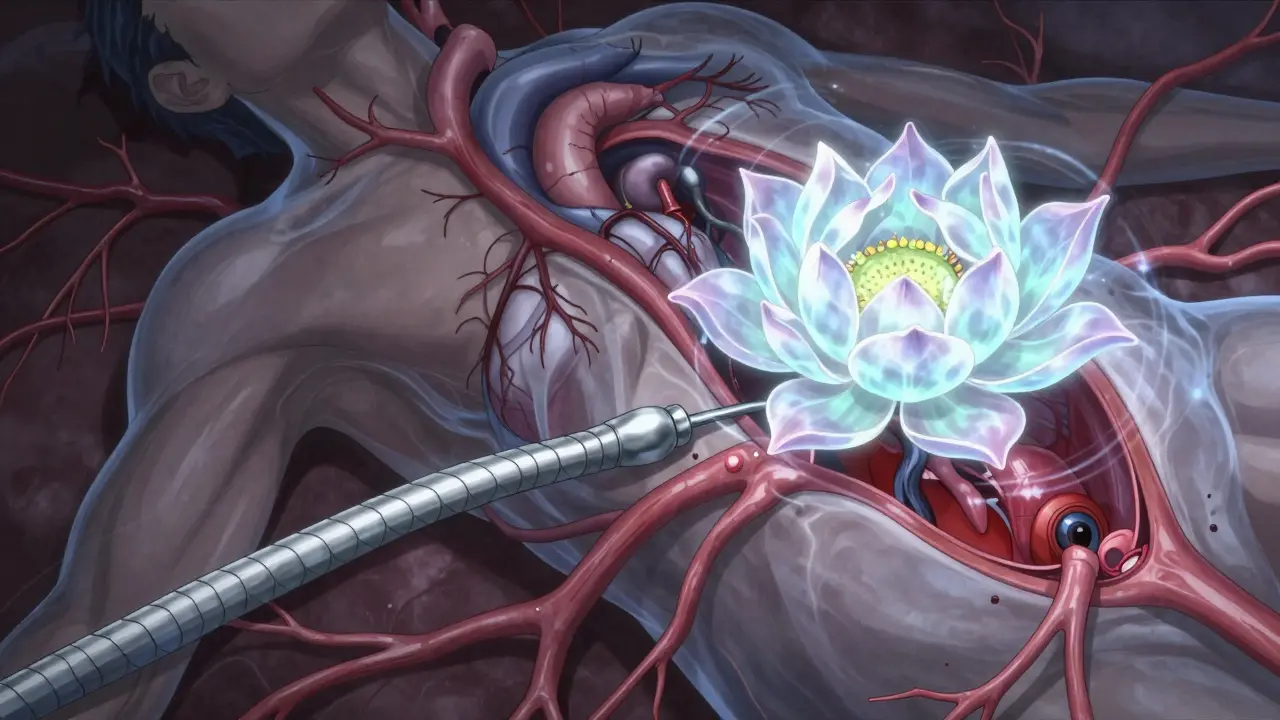

TAVR (Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement) changed everything. Instead of cracking open the chest, a new valve is crammed into the old one through a catheter inserted in the groin or chest. It’s done under local anesthesia. The PARTNER 3 trial showed TAVR had 12.6% lower death rates than surgery at five years for low-risk patients. Today, 65% of aortic valve replacements in the US for patients over 75 are done this way. In the UK, it’s becoming standard for anyone over 70.

For mitral regurgitation, MitraClip is a game-changer. A tiny clip is guided through a vein to grab the leaking edges of the valve and hold them together. It’s not for everyone-only those with severe regurgitation who aren’t good surgical candidates. But for them, it’s life-changing. One patient on Reddit said: “After my MitraClip, I went from struggling to walk to the mailbox to hiking 3 miles daily within two months.”

For mitral stenosis, balloon valvuloplasty can help. A balloon is inflated inside the narrowed valve to stretch it open. It’s not a cure-it often needs repeating-but it can buy years of better quality of life, especially in places where surgery isn’t available.

What Happens After Surgery?

Recovery isn’t the same for everyone. Open-heart surgery means a sternotomy-the breastbone is cut open. That’s painful. One patient on Inspire.com wrote: “It took 8 weeks before I could lift my grandchildren.” Physical therapy starts early, and most people are back to normal activities in 3-6 months.

If you get a mechanical valve, you’ll be on blood thinners like warfarin for life. You’ll need regular INR blood tests-twice a week at first, then monthly. Target levels are 2.5-3.5 for mitral valves, 2.0-3.0 for aortic. Too low, and you risk clots. Too high, and you risk bleeding.

Tissue valves and clips don’t usually need long-term anticoagulation, but you’ll still take aspirin or other antiplatelets. And you’ll need follow-up echocardiograms every year to check for valve wear or new leaks.

The Future: Less Invasive, More Precise

The field is moving fast. In March 2023, the FDA approved the Evoque system for tricuspid valve repair-the first transcatheter option for that valve. Trials are ongoing for the Cardioband and Harpoon systems, which could make mitral repair even more effective.

By 2030, experts predict 80% of valve procedures will be done with catheters, not open surgery. New tissue materials are being developed that could last 25+ years instead of 15. And AI is now helping echocardiographers spot early signs of valve damage before symptoms appear.

The big challenge? Access. High-income countries perform 18 valve procedures per 100,000 people each year. In low-income nations, it’s 0.2. Many people still die from treatable valve disease because they never get diagnosed.

When to Act

Don’t wait for symptoms to get bad. For aortic stenosis, waiting until you’re dizzy or breathless cuts your 2-year survival rate in half. Guidelines now say: if your valve is severely narrowed-even if you feel fine-it’s time to plan for replacement.

For regurgitation, the rule is different. If your heart is still strong and you have no symptoms, watchful waiting is often best. Jumping into surgery too early can do more harm than good. But if your left ventricle starts enlarging or your heart function drops, it’s time to act.

Bottom line: If you’re over 60 and have unexplained fatigue, shortness of breath, or heart palpitations, ask for an echocardiogram. It’s quick, painless, and could save your life.

What’s the difference between stenosis and regurgitation?

Stenosis means the valve is narrowed and can’t open fully, blocking blood flow. Regurgitation means the valve doesn’t close properly, letting blood leak backward. Stenosis forces the heart to pump harder to push blood through; regurgitation makes it pump the same blood over and over. Both strain the heart but require different treatments.

Can you live with a leaky heart valve without surgery?

Yes, for mild or moderate cases. Many people live for years with minor regurgitation without symptoms. But if the leak worsens or your heart starts to enlarge or weaken, surgery becomes necessary. Waiting too long can cause permanent damage. Regular echocardiograms are key to catching changes early.

Is TAVR better than open-heart surgery?

For patients over 70 or those with other health problems, TAVR is usually better-it has lower risk, faster recovery, and similar or better long-term survival. For younger, healthier patients under 60, open-heart surgery with a mechanical valve may still be preferred because it lasts longer. The choice depends on age, overall health, and valve type.

How long do replacement heart valves last?

Mechanical valves last a lifetime but require lifelong blood thinners. Tissue valves (from pigs, cows, or donors) last 15-20 years on average, with about 21% showing signs of wear by 15 years. Newer tissue valves are designed to last longer-some may last 25+ years. MitraClip and similar devices are not replacements but repairs, and their long-term durability is still being studied.

Can heart valve disease be cured?

It can’t be cured like an infection, but it can be effectively treated. Valve replacement or repair restores normal blood flow and lets the heart recover. Most patients return to normal life, with survival rates matching the general population after successful surgery. The goal isn’t just to live longer-it’s to live better.

Johanna Baxter

I swear my grandma had a leaky valve and they just told her to drink more water. Like, wow. Thanks for the life-saving info.

Jacob Paterson

You people act like this is some groundbreaking revelation. I’ve been telling my family for years that if you’re over 60 and out of breath climbing stairs, it’s not ‘getting old’-it’s your heart screaming for help. Still, most ignore it until they’re on the floor. Classic.

RAJAT KD

TAVR success rates in low-resource settings remain abysmal. Access disparity is a moral crisis, not a medical one.

Meghan Hammack

I had my dad’s mitral clip done last year. He went from barely walking to the fridge to hiking with his grandkids. I cried when he said, 'I feel like I’m 50 again.' This isn’t just medicine-it’s magic.

Jerian Lewis

The fact that we’re still using pig valves in 2024 is wild. We’ve got CRISPR and AI, but we’re still stitching animal tissue into humans like it’s 1987. Progress is a myth if it doesn’t reach the people who need it most.

Catherine Scutt

I work in ER. Saw a 58-year-old guy come in with severe aortic stenosis. He’d been told ‘it’s just anxiety’ for 18 months. By the time he got here, his EF was 22%. We saved him-but barely. Stop dismissing fatigue.

Drew Pearlman

I know this sounds like a lot to take in, but hear me out-this isn’t just about valves, it’s about how we treat aging. We’ve normalized suffering in older adults as ‘just part of life,’ but it’s not. It’s preventable. And every time we ignore early symptoms, we’re choosing convenience over compassion. Imagine if we treated every breathless grandparent like they were our own parent. Would we wait?

Kiruthiga Udayakumar

In India, most people don’t even know what an echocardiogram is. My uncle had mitral regurgitation for 7 years before anyone checked. He’s alive now because his daughter worked in a hospital. This isn’t science-it’s a privilege. We need global access, not just fancy tech.

Matthew Maxwell

The notion that TAVR is superior for elderly patients is statistically misleading. Long-term durability data is still insufficient. The reliance on surrogate endpoints in clinical trials obscures true outcomes. One must interrogate the funding sources behind these recommendations.

Lindsey Wellmann

I just got my mom’s echo results back… she’s got mild aortic stenosis. I’m crying. I’m scared. But also… so relieved we caught it. Thank you for writing this. I’m booking the cardiologist tomorrow 💔❤️🩺

Chris Kauwe

The systemic failure here is epistemological. The biomedical model reduces cardiac pathology to biomechanical dysfunction while ignoring the sociopolitical architecture of healthcare access. Valve replacement is a Band-Aid on a hemorrhaging system. We need structural reform-not catheters.