Chronic heartburn isn’t just an annoyance-it’s a warning sign. If you’ve had acid reflux for more than 10 years, especially if you’re a man over 50, you could be at risk for something far more serious: Barrett’s esophagus. This isn’t a condition you can feel directly. You won’t suddenly feel a lump or notice bleeding. Instead, it quietly changes the lining of your esophagus, turning normal tissue into something that can, over time, become cancer. And here’s the hard truth: most people don’t know they have it until it’s advanced.

What Exactly Is Barrett’s Esophagus?

Barrett’s esophagus happens when the cells lining your esophagus change because of long-term exposure to stomach acid. Normally, the esophagus has flat, pink cells called squamous cells. But when acid keeps burning through them, the body tries to protect itself by replacing them with tougher, column-shaped cells that look more like the lining of the intestine. This is called intestinal metaplasia. It’s not cancer-but it’s the closest thing to a warning siren before cancer develops. This change was first described in 1950 by Norman Barrett, a British surgeon at St. Thomas’ Hospital in London. Today, we know that about 5.6% of people in the U.S. have it. Among those with chronic GERD-symptoms like heartburn or regurgitation happening at least twice a week for five years or more-that number jumps to 10-15%. And men are three times more likely to develop it than women. White men with a history of smoking and obesity are at the highest risk.Why Does It Matter?

The real danger isn’t Barrett’s itself-it’s what it can become. About 5% of people with Barrett’s esophagus will develop esophageal adenocarcinoma, a type of cancer that’s aggressive and often caught too late. Once symptoms like trouble swallowing or unexplained weight loss appear, the five-year survival rate drops below 20%. That’s why catching it early is everything. The progression usually follows a pattern: chronic reflux → inflammation → metaplasia (Barrett’s) → low-grade dysplasia → high-grade dysplasia → cancer. But here’s the catch: not everyone follows this path. Many people with Barrett’s never develop cancer. The problem is, doctors can’t yet tell who will and who won’t. That’s why surveillance is so important-and so controversial.How Is It Diagnosed?

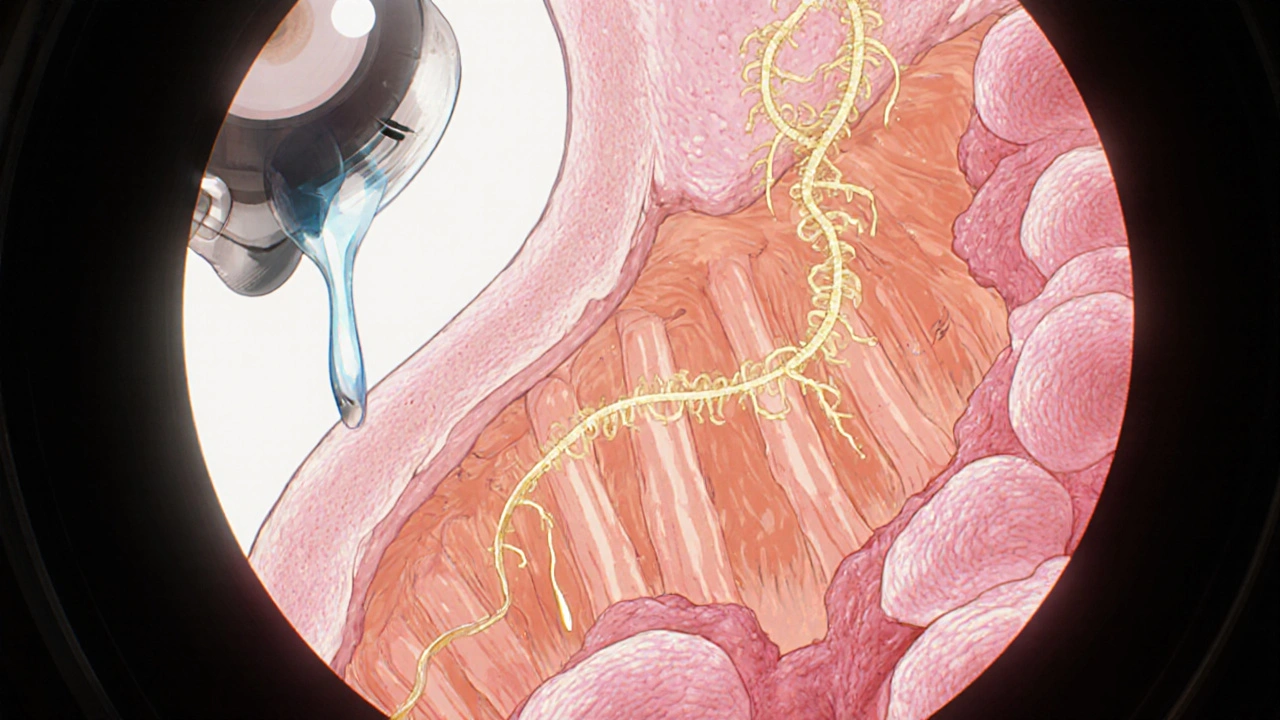

There’s no blood test. No scan. The only way to diagnose Barrett’s esophagus is with an upper endoscopy. During the procedure, a thin, flexible tube with a camera goes down your throat. If the tissue at the bottom of your esophagus looks salmon-colored instead of pale pink, that’s a red flag. But color alone isn’t enough. Doctors must take multiple biopsies-usually 12 to 24 samples-using what’s called the Seattle protocol. That means sampling every 1 to 2 centimeters along the abnormal area, in all four quadrants. Without enough biopsies, you could miss the early signs of dysplasia. The results are then graded:- Non-dysplastic Barrett’s (NDBE): No abnormal cell changes. This is the most common finding.

- Indefinite for dysplasia: The pathologist isn’t sure. You’ll likely need another endoscopy in 3-6 months.

- Low-grade dysplasia (LGD): Early signs of precancerous changes. Needs confirmation by a second expert pathologist.

- High-grade dysplasia (HGD): Severe cell changes. This is the last step before cancer. Immediate treatment is needed.

Who Should Be Screened?

Not everyone with heartburn needs an endoscopy. Screening is targeted. The American College of Gastroenterology recommends it for men over 50 who have had frequent GERD symptoms (at least weekly) for more than five years-and who also have at least one other risk factor: being White, having a BMI over 30, smoking, or having a family history of esophageal cancer. Women and younger men with GERD are rarely screened unless they have multiple risk factors. Why? Because the overall risk is low, and endoscopies are expensive. The U.S. spends about $1.2 billion a year on Barrett’s screening and surveillance. Most of that money goes toward people who will never develop cancer.

What Happens After Diagnosis?

If you’re diagnosed with non-dysplastic Barrett’s, you’ll typically have an endoscopy every 3 to 5 years. That’s it. No drugs, no surgery. Just monitoring. But if you have low-grade dysplasia, things get more serious. In 2022, guidelines changed to recommend treating LGD-not just watching it. Studies show that radiofrequency ablation (RFA) can remove dysplastic tissue in 94% of cases, with results lasting five years or more. RFA uses heat to destroy the abnormal cells. It’s done during an endoscopy. Patients usually go home the same day. Cryotherapy, which uses freezing, is another option. Both have success rates above 90%. After treatment, patients need follow-up endoscopies every 3 to 6 months until the Barrett’s is gone-and then yearly after that. High-grade dysplasia is treated the same way, but more urgently. Some patients even have surgery to remove part of the esophagus, though that’s rare now thanks to effective ablation techniques.Can You Prevent It?

You can’t undo years of reflux, but you can stop it from getting worse. The most important thing is controlling acid-not just your symptoms, but the actual acid exposure in your esophagus. Many people think taking a daily proton pump inhibitor (PPI) like omeprazole or pantoprazole means they’re protected. But studies show that even on standard doses, only 55-70% of patients achieve full acid suppression. That’s why some doctors recommend high-dose PPIs-like 40 mg twice daily-or even 24-hour pH monitoring to make sure your stomach acid isn’t still rising into your esophagus at night. Lifestyle changes matter just as much:- Don’t eat within 3 hours of bedtime.

- Elevate the head of your bed by 6 to 8 inches.

- Avoid fatty foods, chocolate, caffeine, alcohol, and spicy meals.

- Keep your BMI under 25. Losing even 10 pounds can reduce reflux episodes.

- Quit smoking. It weakens the lower esophageal sphincter and reduces saliva production, which normally helps neutralize acid.

The Big Problem: Too Many Procedures, Too Few Answers

Here’s the uncomfortable reality: we screen thousands of people every year, and only a tiny fraction will ever get cancer. That means 95% of those with Barrett’s esophagus undergo repeated endoscopies-some for decades-without ever needing treatment. It’s stressful. It’s expensive. And it’s not always necessary. That’s why researchers are working on better ways to predict risk. One promising tool is the TissueCypher Barrett’s Esophagus Assay, a test that analyzes 16 different biomarkers in biopsy samples. It can tell you with 96% accuracy whether you’re at low risk for progression. Medicare started covering it in 2021. If you have non-dysplastic Barrett’s, this test might help you avoid another endoscopy for years. Another study, funded by the Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas, is testing DNA methylation markers to identify which Barrett’s patients are most likely to develop cancer. If successful, it could cut unnecessary surveillance by 40%.

What Patients Are Saying

On Reddit’s r/GERD forum, people share stories of confusion and frustration. One user wrote: “Three different gastroenterologists gave me three different surveillance schedules for my non-dysplastic Barrett’s.” That’s not uncommon. Guidelines vary. Doctors have different comfort levels. Some recommend endoscopies every 2 years. Others say every 5. It’s messy. But there are also success stories. A patient at Mayo Clinic had high-grade dysplasia and underwent RFA. Six months later, follow-up biopsies showed no trace of Barrett’s. He’s now been cancer-free for seven years.What You Should Do Right Now

If you’ve had daily heartburn for over 10 years, especially if you’re a man over 50, don’t wait for symptoms to get worse. Talk to your doctor about an endoscopy. Don’t assume it’s just ‘indigestion.’ If you’ve already been diagnosed with Barrett’s esophagus:- Make sure your biopsies were done using the Seattle protocol.

- Ask if you’re a candidate for the TissueCypher test to reduce unnecessary endoscopies.

- Don’t just take your PPI and call it done. Ask for a 24-hour pH test to confirm acid suppression.

- Start making lifestyle changes now-even small ones.

Travis Freeman

Man, I never realized how sneaky this stuff is. I’ve had heartburn for over 15 years and just thought it was ‘normal’ because everyone I know has it. This post literally made me book an endoscopy this week. Thanks for laying it out so clearly.

Chris Taylor

Just had my first endo last month for Barrett’s. Non-dysplastic. Docs said I’m good for 5 years. But I started lifting weights and lost 18 lbs. Cut out soda and midnight snacks. Honestly? My heartburn’s gone. You don’t need magic pills if you change your habits.

Melissa Michaels

It is imperative that individuals with chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease be evaluated for Barrett’s esophagus. The American College of Gastroenterology guidelines are clear regarding risk stratification. Many patients remain undiagnosed due to lack of provider awareness and patient reluctance to undergo endoscopic evaluation.

Nathan Brown

It’s wild how we treat symptoms like heartburn like it’s just a nuisance. We’ve normalized suffering. We pop pills like candy and never ask why. What if the real problem isn’t acid… but our entire relationship with food? We eat fast. We eat late. We eat while stressed. We eat junk and then wonder why our bodies rebel. The endoscopy isn’t the solution. The change is.

Matthew Stanford

Good info. If you’re over 50 and have had reflux for years, get checked. No excuses. It’s one procedure. Could save your life. Seriously.

Olivia Currie

OH MY GOD I JUST REALIZED I’VE BEEN HAVING HEARTBURN SINCE I WAS 35 AND I’M 52 NOW 😭 I’M BOOKING AN ENDOSCOPY TOMORROW I CAN’T BELIEVE I WAITED THIS LONG I’M SO SCARED BUT ALSO SO GRATEFUL FOR THIS POST

Curtis Ryan

My uncle had barrett’s and got the radiofrequency thing. He was back to grilling burgers in 3 days. No surgery. No hospital stay. Just a quick burn and boom. It’s not sci-fi anymore. It’s real. And it works.

Rajiv Vyas

Barrett’s? Yeah right. Big Pharma wants you scared so you’ll keep buying PPIs and getting endoscopies. They make billions off this. You think they’d tell you to just lose weight and stop eating at night? Nah. That doesn’t sell. This whole thing is a money scheme. I’ve been off meds for 3 years. Still alive. Still no cancer. Coincidence?

Astro Service

Why do we even care about some esophagus? We got bigger problems. The government’s watching us. The FDA is lying. Just eat what you want. Live free. I’m 60 and eat pizza every night. Still got all my teeth. Still walk. Who cares if my throat burns?